Football's weak-link revolution: Why Mbappé, Yamal and Haaland can't fix flawed teams

PSG and Inter's success in the Champions League suggests that football's quest for the next Lionel Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo may be a misguided one.

Paris Saint-Germain and Inter reaching the Champions League final seriously runs the risk of a number of hot takes dominating the discourse around the state of the modern game. And the one that perhaps interests me the most is that both of these teams are ardent advocates - or at least notable benefactors - of the “weak link theory”.

For those that aren’t nearly boring enough to know what that is, it’s a concept - often referred to as the “O-ring theory” in the analytics world - that stipulates that each team in football is only as good as its weakest player. While some sports, like basketball, are seen as strong link sports, football has recently been seen as a game that is often dictated by the worst player on the pitch, not the best one.

The theory seems to based on a 2002 article in the New Yorker by Malcolm Gladwell, titled “The Talent Myth”, in which the celebrated author essentially pulls apart huge corporations like Enron for prioritising “star” employees over the Average Joe, which then leads to a company that gifts too much autonomy to individuals at the expense of proper organisational structure or team work. It’s not hard to see how this would apply to football or indeed the two finalists of this season’s Champions League.

For example, while PSG certainly do have outstanding players and a wage bill that blows most European clubs out of the water, their ascension to Champions League finalists will inevitably be portrayed through the lens of the club achieving such a feat without Kylian Mbappé. And while it may seem too conveniently to simply say the French giants have reached the highest heights of the competition because they threw off the shackles of star power (Mbappé, but also Lionel Messi and Neymar too), it’s admittedly a narrative that I find far too enticing to ignore.

When we consider PSG’s success in the Champions League over the last 10 years and overlay it with Mbappé’s time at the club, we get a graph like the one above. The club certainly had some highs with the French striker, such as the final in 2020 and two runs to the semi-finals in 2021 and 2024, but rather remarkably the Ligue 1 giants were knocked out of the competition at the Last 16 stage in four of Mbappé’s seven seasons at the club. And in many of those doomed campaigns, the French side were utterly devoid of cohesion and balance within their team, instead attempting to cram as many stars into their front line as possible. The perfect example of the weak-link theory in football.

In my defence, my interest in this theory goes much further back than PSG’s recent trials and tribulations in the Champions League. It first dawned on me during Erling Haaland’s time at Borussia Dortmund. In a truly rare (by modern standards) example of a world class player plying his trade for anyone aside from a handful of super clubs, the Norwegian striker’s remarkable goal haul at the Bundesliga side should have elevated Dortmund’s standing in the German top-flight and indeed in Europe too. But that’s not really what happened.

When we plot Dortmund’s points per game and goals scored per game in the Bundesliga over the course of the last 10 seasons, we get a graph like the one above. The time Haaland spent at the club is marked by the blue area and as we can see it wasn’t exactly a golden era of domestic dominance for the Westfalen club. Dortmund certainly scored a lot of goals - particularly in Haaland’s second full season at the club in 21/22, but the club’s points-per-game hardly budged at all. In fact, if you focus entirely on that black line one could argue that Dortmund actually plateaued in the league despite having the most sought-after goalscorer in the world firing in goals each and every week.

Such a malaise in spite of their world-class talent was also evident in the Champions League. Although the club reached the quarter-finals in 20/21, Haaland’s final season at the club saw Dortmund bow out of the competition in the group stages, finishing third behind Ajax and Sporting. Then, in almost a repeat of PSG’s fortunes when they moved on from Mbappé, Dortmund suddenly found themselves in a Champions League final two years later thanks to Edin Terzic’s dogged and hard-working side whose star player was probably the battle-hardened Mats Hummels in defence or the selfless running of Niklas Füllkrug up front. In no uncertain terms, despite Haaland’s best attempts and his dozens of goals, his star power barely moved the needle in Dortmund’s favour both domestically and in Europe during his time in Germany.

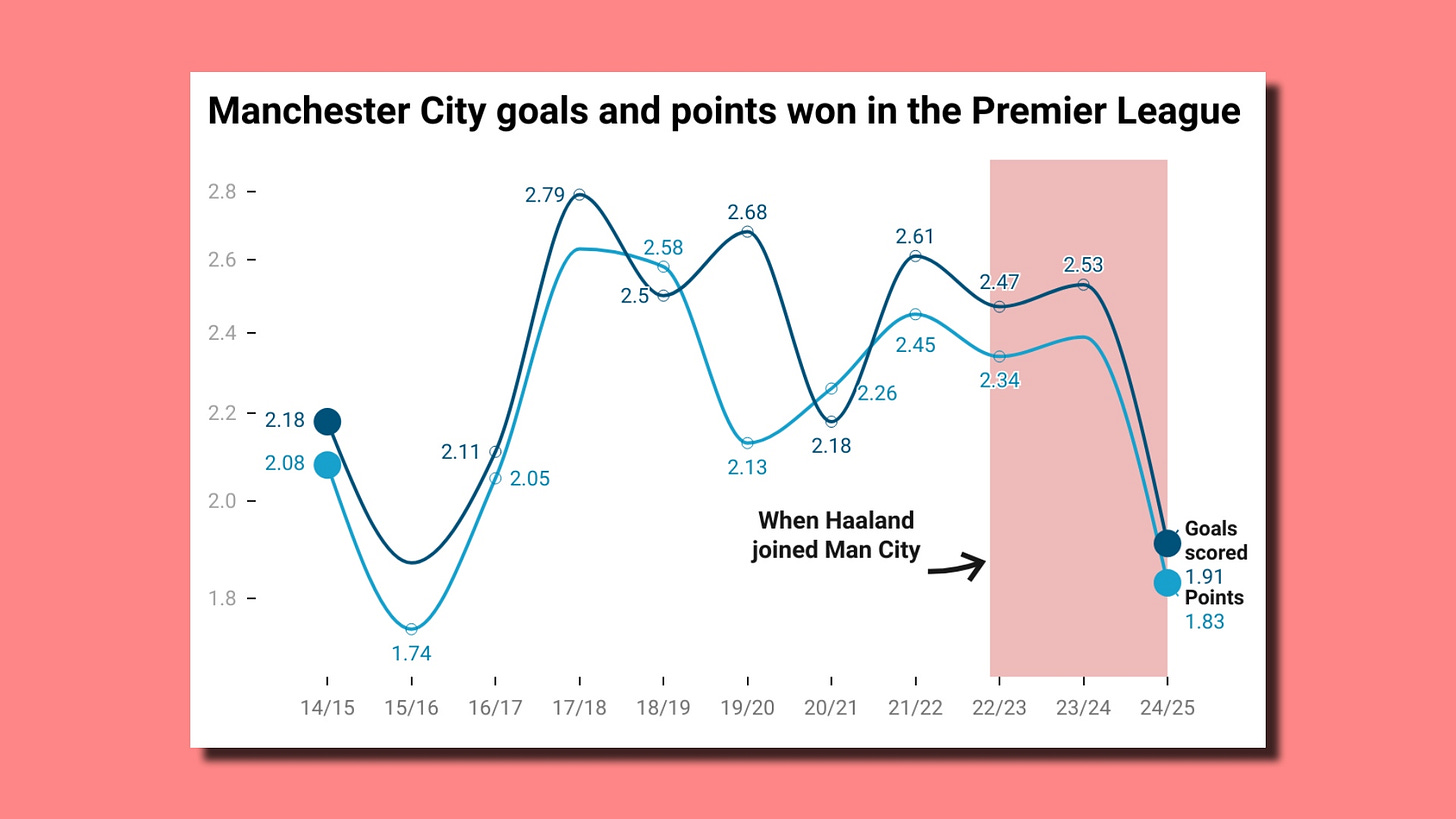

Similarly, we can actually then look at his time at Man City to note a similar trend playing out despite Haaland’s best efforts in front of goal. Although he enjoyed superhuman goalscoring records in his first two seasons at Man City, the club’s goals per game and points per game actually dropped from the 21/22 campaign. And even though the striker has bagged an incredible 24 goals and assists in 29 league games this season, Pep Guardiola’s side have dropped off dramatically in the English top-flight.

Of course, a fair rebuttal to this would simply be the two league titles and the all-important Champions League triumph in 2023 that Haaland has won making the move to England. But in these instances Haaland was part of a remarkably strong and well-balanced team. So much so that Man City won the Champions League in 2023 despite Haaland not registering a single goal or assist in both semi-final games against Real Madrid, or the win over Inter in the final. In this regard, he was perhaps the weakest link of his star-studded team. In this season’s team, Guardiola’s side have clearly suffered from a lack of world class players in a number of positions and as such Haaland’s goals have been unable to compensate for the new weakest links in his team.

Now, it’s important to point out here that this theory doesn’t exist to point the finger at star players and blame them for the flaws in their teams. Instead, it’s supposed to point out that football isn’t won by the best player on the pitch, but is instead often lost by the worst player on it. In Dortmund’s case, the club faltered not through Haaland but because they were playing ineffective players like Nico Schulz and Thomas Meunier on either defensive flank, just as Man City’s team have suffered this season because they’ve been unable to adequately replace Kyle Walker or Rodri. And, similarly, Mbappé’s PSG routinely slipped up against the very best teams because they were always set up to prioritise the best players at the club, rather than protect their worst ones.

This, naturally, brings us back to this season’s finalists. If there was ever a team that exemplified the pursuit of making as few errors as possible it is Simone Inzaghi’s Inter side, who effectively overcame Hansi Flick’s high-flying Barcelona team with the same tactics that have been knocking out top-heavy PSG sides in Europe for much of the last 15 years. The Italian side didn’t win that tie because they did enough to stop Lamine Yamal. They won it because Flick’s high line continuously pushed his young and inexperienced defence to the limit, leading to Pau Cubarsí giving away a penalty with a rash challenge and Inter scoring two counter-attacking goals.

In their 2013 book “The Numbers Game”, Chris Anderson and David Sally make a somewhat grim but illuminating comparison between football and space travel to underline what they came to call the “O-ring theory”: “Football is a weak-link game. Like the space shuttle, one small, malfunctioning part can cause a multimillion-pound disaster.” And while I’m not quite sure we should be comparing sport to such drastic scenarios, the metaphor certainly makes sense.

What’s so fascinating about the real-life application of such a theory is not only how it underlines the folly in overlooking second-string full-backs or ageing midfielders in favour of spending more money on star wingers and strikers, but also why Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo were so special when they were in their prime. Unlike Mbappé, Haaland or Yamal, Messi and Ronaldo did seemingly have the capacity to win games almost single-handedly. And as a result overcome the inherent flaws in their teams.

Perhaps it takes a true great to break free of the economic and sporting laws that govern our game. And if so, that feels like a fitting test for the young stars of today to overcome if they really hope to be compared to the fantastic duo. But for now, European football may need to bunker down for a period without the kind of individuals that can rewrite the rulebook at will. This season’s Champions League final may end up being a dull affair, but the manner in which PSG and Inter got there is utterly fascinating.

Great article. As a Dortmund fan, I’ve been confused at their lack of diligence in getting a solid roster with depth all these years. With better roster planning, they could have made their years with Sancho, Bellingham, Dembele, Haaland, etc. count more with actual trophies - at least two Meisterschales.

Excellent article and very apt. An excellent riposte to those who say that Modern Football has become a bit "too robotic" and predictable. We have the statistical reason why coaches should focus on steady consistent performers, rather than flashy show ponies. Messi and CR7 really were 'unicorn players' who did not fit any model; their individual performances were off the charts and almost uncontrollable at times.

However, it feels a little simplistic to use Haaland as an example, especially as he was saw young and raw at Dortmund, particularly in his first season. Then he joined Man City when they were already appearing to decline despite their amazing points total in 2022. Haaland is not a great team player which is incontrovertible, but his role was never to help that team gel but it was to dominate opposition CBs and finish off moves. In my view, he really did push Man City onto their Champions League win and the 'treble' the following season despite the declining powers of KDB and Gundogan. Late career Neymar and Mbappé are the best examples of 'weak-link stars' as they are both rather problematic individuals not only in their work rate off the ball and their lack of positional discipline but also the media circus that surrounds them. So the disruption they create not only has a statistical metric but also a psychological and social one too.

Mbappé has demonstrated time and time again that he can score outrageous goals and high-profile hattricks but he is not yet a unicorn. If Alonso does take over at Real Madrid he will have to address this Mbappé issue head on, otherwise it will be impossible for Madrid to succeed.